The Anderson and Lyness Collection

Exhibition dates: 17 July - 13 October 2019

The Anderson Lyness Collection

17 July to 13 October / The Anderson and Lyness Collection

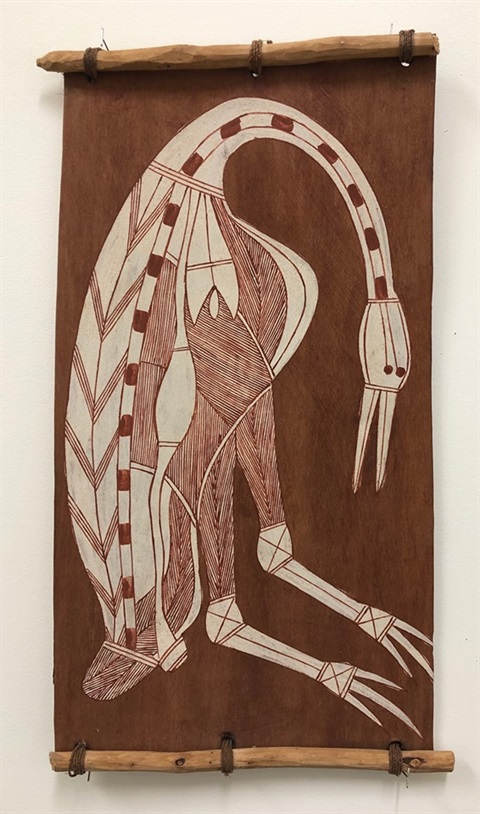

The Anderson and Lyness Collection was built over the 1970s and 80s by the parents of Helen Lyness (nee Anderson), and later Helen and Alan Anderson, when they lived at Oenpilli with the Kunwinjku (meaning fresh water people) in the Northern Territory. Comprising of 30 pieces, the collection includes significant examples of bark paintings, tools and basketry and was kindly donated to the Gallery in 2017.

A Brief Reflection - Alan Lyness

Between 1979 and 1982 I had the honour of living at Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) which is situated in western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. This land is the traditional homeland of the Kunwinjku people; Kunwinjku meaning fresh water people. As well as the township of Oenpelli the Kunwinjku people inhabit traditional lands (outstations) that are primarily accessed in the dry season and are spread over a wide geographical area. Oenpelli acts as a hub. The area is scenically magnificent with a majestic escarpment dominating the landscape with wide open plains, forests, billabongs and an abundance of wildlife to take your breath away. During the wet season Oenpelli typically accommodated up to 800 Aboriginal people and a small community of Europeans, or Balunda as we are known. The township of Oenpelli is cut off during the Wet season for up to five months.

At that time the Kunwinjku people still possessed and lived within the context or their rich Aboriginal heritage; English was still then very much a second language. It was so good to see the language intact and used as we would use English to communicate. Their culture also maintained the complex social structures that are quite foreign to our thinking. For example there are eight skin groups and two moieties and those groupings dictate who one can marry or form other relationships with. In some cases some people in certain relationships are forbidden to communicate with each other at all. Incidents of pointing the bone to resolve conflict or punish individuals was confronting.

Before my wife and I arrived in Oenpelli she had spent her teenage years in the community and had built many connections with the Aboriginal people. As a mark of acceptance the Aboriginal community over time would confer on some European residents a skin grouping which then enabled Europeans to connect with the Aboriginal community in a more intimate and personal way. For instance, because my wife had previously lived in the community and was a trusted member she had been given the skin grouping called Ngalwakadj. This meant that my skin grouping would be limited to one of two others, I was conferred with the grouping Nawakadj. Note the prefix at the front of the skin grouping denoted male or female ie; Ngal – female and Na – male.

Whilst at Oenpelli I was employed by the Department of Education in the Bi Lingual education program at the local school. This program sought to teach the Aboriginal children to read and write in their own language in primary as it was much easier for them to learn the principles in a language known to them. In high school the program centred on developing literacy skills in English which produced students on graduation who were bi-lingual. This served the purpose of maintaining their heritage in written form as well as spoken.

I had the privilege of assisting to produce reading primers in the local language. This often meant accompanying Aboriginal elders and school children on hunting trips where photos were taken and stories produced about these adventures. Trips to collect turtles, eggs from wild geese, file snakes and barramundi from billabongs, possums and honey from native bee hives were just some of the activities undertaken and reproduced in story books.

Apart from all this living at Oenpelli was the ultimate adventure. The border of Kakadu National Park was close by though the park in many ways was dull compared to the natural landscape of Oenpelli and surrounds. The whole area was a natural wonderland and I often thought it compared to some of the wildlife shows I had seen on Africa. During my time there many wonderful friendships were built with Aboriginal people. I came to appreciate their deep ties with the land and their spirituality, some of which was confronting. Their skills in the bush were something to behold and it was good to be in a position where I was incompetent in their domain. Much laughter was enjoyed by my new friends as I tried my hand during various hunting trips. Three years that were treasured and will never be forgotten.